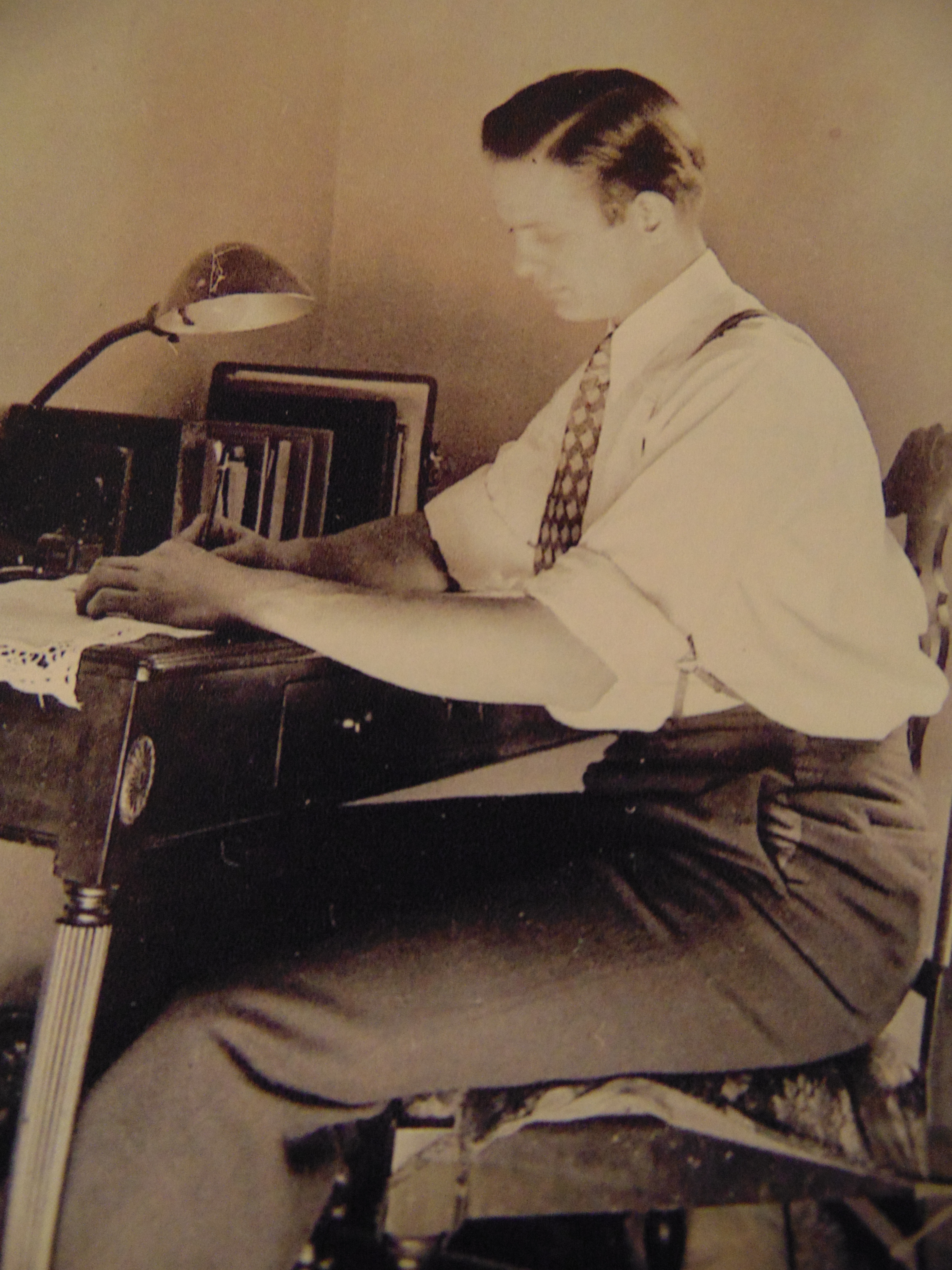

Yes, that’s my father in the pictures: Dad with me; Dad conducting earlier in his music education and performance careers; Dad writing at his desk or perhaps arranging music when younger; and in a much later portrait with Mom, I think in their mid-to-late seventies and perhaps taken by my brother (a photographer). I have reason to thoughtfully remember him today, and it’s not only because Father’s Day is soon. Or even because he happened to have died in June at age 83 when I was 42. He died after failed recovery from a quadruple heart bypass operation.

Rather, it was a social media group I follow that highlights all things historical regarding Midland, Michigan, my old hometown. They posted some of his photos, and a fairly large number of people responded. He was very fondly remembered, praised, and valued in the community and their lives as youthful musicians, and more. One doesn’t forget some individuals years later but recall memories with affection and fine words. Lawrence Guenther was that sort of man. He is thought of many decades later as being kind, patient, encouraging, steadfast, capable, caring.

It has been so long since Dad was alive that I only occasionally enjoy memories flooding my mind. That may be when hearing certain classical or big band music; watching my son’s hands when he makes something or talks with expressiveness (like my Dad’s); or revelling in a grandson’s tinkering with old cars–which his great grandfather also loved to do in his spare time; noting a daughter’s big blue eyes, so deep and absorbed by what is looked at like Dad’s. (All my kids are musical, as well.)

Once I nearly wept when a man ahead of me in a store was buying ice cream and I felt Dad’s presence sweep over me. That stranger’s height, his good hands, that butter pecan ice cream, his friendly banter with the sales person. My father loved ice cream; he was tall enough but exuded a much bigger energy of life; and his hands were strong and beautiful. He chatted with and smiled at most everyone he ran across. I used to stand back and watch and listen to him interact. Or direct or perform music with intense focus and profound love.

On Father’s Day, perhaps I will ask my adult chidren what they remember about their grandfather. And in the meantime I have accessed lovelier memories of who he was and how he cared about me and his (our) extended family. Those mental pictures of him in coveralls or tuxedos, the old conversations: little movies of us doing this or that together, that are held close. I have written about him several times in this blog and elsewhere. (A personal essay about our shared experience of finding a hidden treasure in an attic– a cello–and his purchasing that cello for me was nominated for a Pushcart Prize, which is an honor I appreciate.)

Lawrence Guenther’s presence could be frankly charismatic. He was made for public life, loved meeting others, had a gift for teaching, was a public speaker who entertained and held listeners’ attention. He was a natural teacher and conductor, and enjoyed performing in the symphony, trios or quartets with his violin or viola. In college he played at least alto saxophone and clarinet while in dance bands. He played several more instruments and could just pick those up and play even as he aged. As a conductor, he fairly danced as he cued each section and brought forth concise and emotional dynamics in the score, and persuaded the best performance each musician could give.

I look more like him than my mother: large blue eyes (also in need of glasses, then contacts), my aging skin prone to deeper lines, dimples, wavy hair (though Mom had wavy hair, too). And I was born musical– as all my siblings were (though I left music behind after various life occurences). Dad loved to write, as well, though it was mostly about subjects he studied or his passion for music. And deep love and respect for his wife. His birthday and other cards to her illuminate his poetic nature. His caring for her was apparent by the way he wrapped his arms about her, kissed her cheek or neck, and enjoyed light repartee with her. He praised her beauty and many talents. And he also spent alot of time reading–musical scores, history, other nonfiction books. And he studied his Christian faith seriously, and shared meticulous notes with his Bible study classes. (He also directed the church choir a long while.)

But was he a good father? What contributes to that general moniker?

The times in which I grew up would define him as such and often still do: he was a very hard worker who worked more than one job to care for us all, keep us well settled in an educated middle class home; was extremely careful with money so that his wife would remain secure in the event of his death. He was a strict parent who only had to look at us to get his point across; a provider of a good home and food, some travel times and other pleasing privledges. He played indoor or outdoor games (and created a few) with us although he wanted to win every time. And he coached us as we practiced our instruments. In my case, when I sang and played my cello. A particularly fond memory: how happily he’d accompany me on our baby grand piano after I chose one of the old jazz standards. I sang out well, and he seemed to like my singing; at times he sang harmony.

But was he a good father, was he there for all five of us siblings? Was he there for me, the last of the lot? He was literally gone a great deal, working, working. I was more fortunate than older siblings, I suspect. They each left for university and then I was home alone the next several years. I have memories the others don’t have, whether it was because they weren’t clamoring for his attention and so I got a bit more–or whether I was determined to follow him around whenever he was home. I liked to hang out with him (and my mother) when I had little else to do.

I was pleased to run and get tools he needed from the garage while he disappeared under the hood of a cranky car, then would watch and ask questions. I was delighted to go down to his basement instrument repair shop and watch his fix cracked violins or hairless bass bows or sticky keys on an oboe. And I liked playing Scrabble, dominoes, checkers and rummy with him even if I lost. And was more than excited to ride behind him on his noisy “motorbike” when he went on an errand–despite the stripe of fiery blisters on my leg as bare skin momentarily grazed the engine (which made my mother furious with him). I loved that he had such awe for nature; that we had campfires and went out on the rowboats or sailboats of friends’. He had a sense of adventure, enjoyed travelling and talking about the history (and composers, especially in Europe) of each place.

But I also was intimidated b y him. Not scared because he had a terrible temper or was mean spirited. He was slow to anger and did not physically discipline me except a couple times as a kid. He was so well known and appreciated. I was anxious about his expectations as well as the respected name of our family. The goals seemed so high I thought I’d never meet him no matter how hard I tried. I feared failure terribly, feared even a letter grade below an “A”, or a music competition award less than the best. He was nearly always critical of our music playing, and our studies and grades were parmount, too. he tried to teach us to reach for the pinnacle of our best. The best. He asked for perfection as very nearly so as he believed it was possible. I should play that measure much better or write that sentence more succinctly. I must do that bar or assignment again and again until it was done right. I was not to ever waste a talent. I was not to err when I knew better and should aspire to the highest possible state. I believed him. I wanted it, too. But it still scared me, that fast descent which came from a failure to meet the goal.

The “best” meant to excel, to pursue excellence for one’s talents and behavior. That was my motto by age 12: “Excellence Above All”. I wrote it in my notebooks and journals and on my arm in ink once. I had faith that it could happen, and strove for it daily. Superior behavior was ascribed to reasonable emotional responses in life; good physical activities and choices; intellectual pursuits; and spiritual development. Temperance was important. Holding informed, intelligent conversations was desired. Being decorous and poised were givens. No swearing allowed, of course no alcohol use (or drugs, of course) tolerated. And I was not to leave the house in that miniskirt! Or listen to blues, folk or pop music–certainly not in his house. Life in our home was orderly more often than not, steeped in the traditional fine arts, centered in prayer and appropriate behavior. “Civilized”, as my parents deemed it.

And, of course, we all must finish university degrees, graduate preferably with honors and then naturally find a respectable job and carry on well. And if at all possible, play our musical instruments professionally.

Our father was fully supportive of his daughters, as well as sons, being well educated–somewhat forward thinking in the fifties and sixties. I don’t recall I spent much time in the kitchen learning to cook or engaging in housekeeping–despite my mother being a teacher, as well. (I was expected to help them with entertaining friends who came, from serving them at times to conversing well.)

But Dad was not too emotionally engaged with me or my siblings the majority of time. He came home exhausted many days, and as he aged (he was over 40 when I was born) he’d fall asleep in his chair while reading the newspaper. But though we did enjoy some actitivies together–especially when it was his choice–he wasn’t about talking over personal issues. Dad was oblivous a great deal, and so he had little idea who I was becoming or what mattered the most to me as I became an adolescent. He knew what I did well and accomplished–that I was a budding figure skater, that I was deeply in love with music, was an honor roll student, that I wrote as much as I could and liked to draw, and performed in plays and musicals. And he showed up when he could, which was perhaps not quite often enough; and his feedback showed up with him. But there were times he praised my efforts and it made me happy.

Yet he never knew what I suffered nor the long lasting extent of it, due to at least two years of long time childhood sexual abuse by someone very close to our family. At times, when my behavior seemed reckless or just ill-conceived he seemed to think I was being foolish or rebellious for no reason or, later, perhaps entirely deranged. Just once he asked me what was going on after I got in trouble in high school for slapping a girl and he was called in to get me. I had terribly embarrassed him, distressed him. I turned away from him, ashamed, angry and confused. I wanted to say, “Why bother now? You are asking too late. And I cannot tell you.”

I was forty before I decided to write a letter to my parents about the past and my evolving present when a divorce was impending. I partially explained the causes of ruination of my life and my slow, arduous work that was taking me towards true well being. That I had had more therapy, claimed full sobriety– and my loving friends’ and sisters’ support.

I thought he had more or less known of my situation as a child and beyond, and was distraught that he never rescued me. I used to will his presence for help. But I learned that my parents’ seeming abandonment was possibly the worst of what had happened to me. If they had helped me, had defended and protected me, I would surely have lived a different life. If they had known that it was childhood years followed by my teens, into adulthood: more assaults occurred, perpetrated by strangers, by men I dated, by a spouse… Would things have changed depending on what my father –and mother–might have known and done at that time? Yet, I had accepted that it was up to me, even from the start, to save myself from the predator. I had to insure that his threats of great harm to my family and me if I spoke of it never came to pass. So I was clear even as a child I was on my own. I knew it more entirely by 20, 30, 40–but then found out I didn’t have to live a hard life alone. (And one sister, also abused a few times, told me the convicted predator had ended up in prison.)

It was difficult to believe I could be worth the trouble to help, to love without judgement if at all. But I discovered I might be. I was beginning to hope for that.

After that letter I visited my parents. The most general facts had been given. Over the years I’d suffered from PTSD I had been sent to foster care, put in my own apartment at age 17, hauled off to psychiatric units, flown far away to my sisters’ homes– to get me out of their lives, I was quite sure rightly or or wrongly. To not cause them such embrassment and sleepless nights of anxiety, a lack of peace in their living. Sent away and away. They had not approached me with careful questions, not since my father had tried once to find ouot something. I had done well in many ways, oddly, but finally it had caught up with me, the split life of victimized child/youth v. achiever teen. No one had told them what was wrong and everything got more dire. I was so-called therapeutically treated then plied with more drugs– then finally set free into a world where I would live looking over my shoulder. Vigorously guarding my heart and soul. Keeping more to myself unless I could control an uncertain situation. It was 1969 and no one held community support groups; no one spoke out about victimization, few if any wrote memoirs about their recovery from hellish times.

But finally they knew a bit of it, and could not deny the realities I had survived. How does a daughter tell her parents the horrible things that had happened for years? Impossible; it felt almost terrifying to do. But I could write of some of it down; then I could keep it at a distance. It took enough out of me to state that there also had been recurrent later assaults.

What saved me was this: that my father sat before me and was overcome with outrage and anguish. It was brief but overwhelming, his response. But it was humane, fatherly, powerful and it was a reclamation for me. It told me he had been entirely ignorant of the causes of my various troubles. It was a starting point of a reconcilliation of sorts.

My mother, too, showed shock and despair.

It was very, very hard.

I felt like an utter failure, felt shame that I could not erase, and I was not nor would I ever really be who they had hoped I could become. Who I had hoped to become as a child and young adult; accomplished in the arts and emerging with a degree or two from college; morally and spiritually intact; successful in the world, at large. I felt I had somehow failed myself in the process of staying alive long enough to reclaim and hold onto basic strength, persistence and the sanity underneath it all. But I still wanted to be the daughter they admired and accepted without reservation as they did my siblings.

Somehow I felt somewhat salvaged because I knew they both had, in actuality, probably loved me and perhaps more than I realized. That they didn’t know what all happened. And that my refined yet still ordinary father would have stepped in and protected me, done what he could to make the needed difference in my childhood, in my life. And, too, my mother would have been empathetic, and present in different ways. We could have survived it, all together; they would have been there for me if they had known, perhaps known sooner. Why they did not seem to get any information those years, I do not know. It was not the twenty-first century yet and some topics were considered too tabu. People didn’t share turmoil and trouble. And I was silent out of fear- for my life, my family’s. And later, speaking was not even considered an option. One learns how to be mute. It is a hard habit to undo.

But that day Dad’s immediate reaction began to heal me. He had always seemed to be a man of honor. And he was. It helped my soul to stop clenching, my mind stop burning up with pain, grief. I knew he would become silent again, that we would not mention it again–it was just his way. But hugs were warmer, his words were gentler despite further hard times. (I found a way to make peace with my mother over time. We’d been close in some ways but after that day we created bridges for a healthier connection.)

My father was at his core a genuine, good man, you see, an oddly simple though brilliant man, a righteous man who loved fiercely but who suffered from perfectionism (and passed it on), and who wanted only the best for his children as well as for himself. For him, life was family, music, and God plus a great curiosity about the world, the sciences and nature’s ways. He had been raised by parents expecting that same high bar of their children, Dad and my two uncles–and they all had fine successes. (And my paternal grandfather holds a special place in my heart– more than grandmother, a quiet, dependent woman due parttly to that time and place they lived within).

But life is not just achievement, accolades and that ever-present “look good”. I don’t need to prove myself to anyone, anymore and if I back off from trying something, I ask–is it fear of failure or is it lack of interest or time?

Living a human life embraces blood and bone and sinew; the mysterious well of heart and font of spirit; wild desires and wounding losses; of dreams fed and starved and relationships that mean more than can be described and finding some end in betrayals or slow decay. It is intense, it is gorgeous and miserable–and it manifests in a myriad ways. Families need to offer love to their own, period. And as a mother I must trust intuitions, keep faith, never give up, care without ceasing.

What makes a good father, then? A man who shares activities with his kids and looks for their engagement; who expects good things even when there are failures; who is humble in demeanor, mostly even-tempered and strong-hearted. A man who can say I’m sorry and I will stand by you.

A man who can say: “I would have been there for you!” when he discovers he was, grievously, not. The kind of man who looks at his daughter and sees her suffering and her love and loves her back, in his own ways, and without question.

Or that is what I believe. And that is what carries me when I think of the most trying times and then of my mysterious, smart, introverted, devoted father. I know we had happy times, too. I carry a bit of his spirit with me and it all counts for something good in the end.

Happy Father’s Day; may you be blessed with love.

You must be logged in to post a comment.